The Digestive Process and Food Coloring: Can Blue Food Coloring Cause Green Stool

Can blue food coloring cause green stool – The journey of food coloring, such as blue food coloring, through the digestive system is a complex process involving various stages of breakdown and absorption. Understanding this process helps explain why the color of stool might change after consuming foods containing artificial coloring. The body doesn’t recognize food coloring as a nutrient; instead, it treats it as a foreign substance to be processed and eliminated.The chemical breakdown of blue food coloring begins in the stomach.

So, you’re wondering if that blue food coloring could be turning your stool green? It’s a fascinating question, and it reminds me of a fun experiment I once did – check out this awesome milk and food coloring experiment to see how colors interact! Anyway, back to your poop: while blue food coloring can sometimes lead to a greenish hue due to how your body processes it, it’s not always the case.

Many factors influence stool color.

The highly acidic environment of the stomach (pH approximately 1.5-3.5) can affect the stability of some food coloring molecules, potentially causing some degradation. However, many synthetic food colorings are designed to be relatively stable across a wide range of pH levels, meaning they may survive the stomach largely intact. The specific chemical changes depend on the type of blue food coloring used – different dyes have different chemical structures and varying degrees of stability.

For instance, Brilliant Blue FCF (a common blue dye) is relatively resistant to acid hydrolysis.

Food Coloring Absorption and Processing

Once the food coloring passes through the stomach, it enters the small intestine, the primary site of nutrient absorption. Here, the process of absorption is largely passive, meaning the food coloring molecules move across the intestinal lining based on concentration gradients. The small intestine’s large surface area, due to villi and microvilli, facilitates this absorption. The absorbed food coloring molecules then enter the bloodstream and are transported to the liver.

The liver plays a crucial role in metabolizing and filtering various substances, including food coloring. Some food coloring molecules may be further broken down in the liver, while others might be excreted relatively unchanged. The rate of absorption and metabolism varies depending on the specific food coloring, the individual’s metabolism, and other factors. A portion of the unabsorbed food coloring passes into the large intestine, where it eventually contributes to the color of the stool.

The green color sometimes observed may result from the interaction of the blue dye with the naturally occurring pigments in the bile or the bacterial flora in the gut, causing a color shift.

Factors Affecting Stool Color

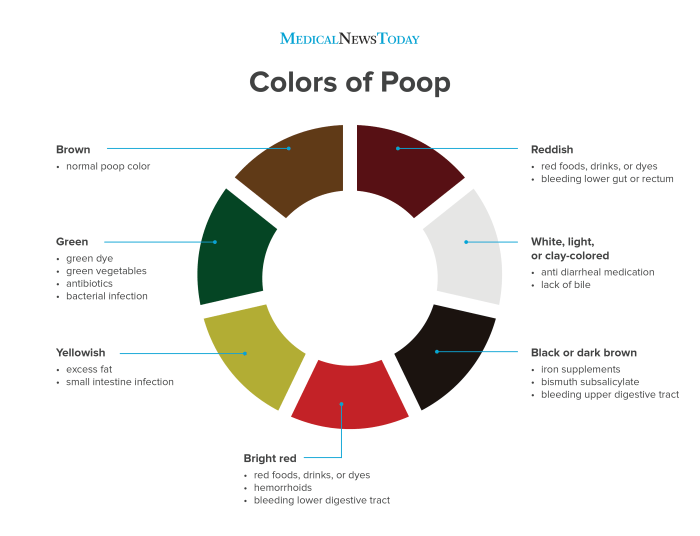

Stool color, while often brown, is a surprisingly dynamic indicator of various internal processes and dietary habits. Numerous factors beyond the ingestion of blue food coloring can significantly alter the appearance of feces, providing valuable clues to overall health and recent dietary intake. Understanding these influences is crucial for interpreting any changes in stool color and differentiating between harmless variations and potential health concerns.Several factors, besides food coloring, influence stool color.

These include dietary intake, medication, and underlying medical conditions. Dietary components rich in certain pigments directly impact the color of stool, while medications can sometimes alter bile production or intestinal transit time, affecting the final product. Similarly, certain medical conditions can alter digestive processes, resulting in changes to stool color and consistency.

Dietary Influences on Stool Color

The most significant influence on stool color is diet. Foods containing various pigments and fiber content alter the final color and consistency. For instance, a diet rich in beets can lead to a reddish hue, while a diet high in leafy green vegetables may result in a greener shade. Conversely, a diet low in fiber can produce darker, harder stools.

The interaction of these dietary pigments with bile pigments further modifies the final color.

The Impact of Medications on Stool Color

Many medications can influence stool color. For example, some antibiotics can cause changes in gut flora, impacting the breakdown of bile pigments and potentially altering stool color. Iron supplements are notorious for causing dark, even black, stools. This is due to the presence of unabsorbed iron in the gastrointestinal tract. Other medications may have less predictable effects, depending on individual metabolic processes and the specific medication.

The Role of Bile Pigments in Stool Color, Can blue food coloring cause green stool

Bile pigments, primarily bilirubin, are the primary determinants of the characteristic brown color of normal stool. Bilirubin is a breakdown product of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells. As red blood cells age and are broken down in the liver, bilirubin is produced and eventually excreted in the bile. In the intestines, bacterial action converts bilirubin into stercobilin, which is responsible for the brown hue.

Variations in bile production, liver function, or intestinal bacterial activity can alter stercobilin levels, resulting in changes to stool color. A deficiency in bile production, for example, can lead to light-colored or clay-colored stools.

Examples of Food and Their Effects on Stool Color

| Food Type | Expected Stool Color | Contributing Pigments | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beets | Reddish | Betalains | The intensity of the red color depends on the quantity consumed. |

| Spinach | Greenish | Chlorophyll | May be less noticeable if consumed in smaller quantities. |

| Blackberries | Dark Purple/Black | Anthocyanins | The color may be less intense after digestion. |

| Iron Supplements | Dark, almost black | Unabsorbed iron | This is a common side effect and usually harmless. |

The Science Behind Green Stool

The transformation of blue food coloring into a green hue within the digestive system isn’t a simple matter of pigment alteration. Several complex factors, including chemical reactions, bacterial interactions, and the influence of gut pH, contribute to this color change. Understanding these processes provides insight into the surprising results sometimes observed after consuming blue-colored foods or drinks.The appearance of green stool after ingesting blue food coloring is primarily due to the interplay of several chemical and biological processes within the digestive tract.

While blue food coloring itself doesn’t directly transform into green, its interaction with the environment of the gut, including the pH and the gut microbiota, can lead to a shift in its spectral properties, resulting in a perceived green color.

Chemical Reactions and Pigment Alteration

The chemical structure of blue food colorings, often synthetic dyes like Brilliant Blue FCF, can be affected by the acidic environment of the stomach. The pH of the stomach is typically highly acidic (around 1.5-3.5). This acidity can potentially alter the chemical bonds within the dye molecule, leading to a change in its absorption and reflection of light. While not a direct conversion to green, these changes in the molecule’s structure could shift its spectral properties towards the green portion of the visible light spectrum, making the stool appear greenish.

This process is not fully understood and requires further research to determine the exact chemical reactions involved.

Interaction with Gut Bacteria

The human gut is home to a vast and diverse population of bacteria. These microorganisms play a crucial role in digestion and nutrient absorption, but they can also interact with ingested substances, including food colorings. Some gut bacteria possess enzymes capable of metabolizing certain dye molecules. These metabolic processes might alter the chemical structure of the blue dye, causing a change in its color.

The specific bacterial species involved and the precise metabolic pathways remain areas of ongoing research. For example, certain bacteria known to produce pigments themselves might interact with the blue dye, potentially leading to a green color through a combination of the original dye and the bacterial pigments.

Role of Gut pH

The pH level throughout the digestive tract varies significantly. The highly acidic environment of the stomach is followed by a more alkaline environment in the small intestine and a slightly acidic to neutral pH in the large intestine. Changes in pH can influence the ionization state of the blue food coloring molecule. Different ionization states can affect how the molecule absorbs and reflects light, thus impacting its perceived color.

A shift towards a more alkaline pH, for example, might favor a chemical form of the dye that appears greener than its acidic form. The transit time of food through the digestive system also influences the extent of pH-related color changes. Faster transit times may limit the extent of pH-induced color alterations.

Visual Representation of the Process

Understanding the visual changes of blue food coloring within the digestive system requires considering its chemical properties and the dynamic environment of the gastrointestinal tract. The journey of the dye, from ingestion to excretion, involves a series of transformations influenced by pH changes, enzymatic activity, and interaction with gut microbiota. These changes can be represented visually in several ways, highlighting the key interactions and resulting color shifts.The following visualization depicts the progression of blue food coloring through the digestive system.

Imagine a series of panels, each representing a different stage. Panel 1 shows the initial ingestion of the blue dye, appearing as a vibrant, uniform blue solution. Panel 2 depicts the dye entering the stomach, where the acidic environment (pH ~1.5-3.5) begins to alter the dye’s molecular structure. This might cause a slight shift towards a purplish hue, depending on the specific dye used.

Panel 3 shows the dye entering the small intestine, where the pH becomes more alkaline (pH ~6-7). Here, the color shift might become more pronounced, possibly moving toward a greenish-blue or even a slightly more muted blue. Panel 4 illustrates the dye’s passage through the large intestine. Bacterial metabolism and further pH changes could lead to a range of color variations, potentially including a more pronounced green or even a brownish hue depending on the interaction with bile pigments and other fecal components.

Finally, Panel 5 shows the excretion of the dye in the stool, reflecting the cumulative effect of all the preceding transformations. The final color could vary significantly based on individual factors such as gut microbiome composition and transit time.

Microscopic Interaction of Gut Bacteria and Blue Food Coloring

A microscopic view would reveal a complex interplay between gut bacteria and the blue food coloring molecules. Imagine a field of view teeming with diverse bacterial species, each with unique metabolic capabilities. The blue dye molecules, initially dispersed, would gradually come into contact with various bacterial cells. Some bacteria might actively metabolize the dye, breaking down its chemical structure and leading to color changes.

This process could involve enzymatic reactions that alter the dye’s chromophore (the part of the molecule responsible for color). Other bacteria might simply interact passively, influencing the dye’s overall distribution and appearance within the gut lumen. For instance, the presence of bacterial biofilms could cause the dye to accumulate in certain areas, creating localized variations in color intensity.

The visualization would show a dynamic scene of molecular interactions, with the blue dye molecules undergoing transformations and interacting with the diverse bacterial community, ultimately leading to the final color observed in the stool. The microscopic image might show areas of concentrated blue, areas where the color is fading or shifting, and areas where the dye has been fully metabolized, resulting in a colorless or differently colored product.

The variety of bacterial shapes and sizes, interacting with the dye molecules in different ways, would emphasize the complexity of this interaction.

Questions Often Asked

Is it harmful if my stool turns green after eating blue food coloring?

Generally, no. A temporary change in stool color due to food coloring is usually harmless. However, persistent changes or other symptoms should prompt a consultation with a doctor.

How long does it take for the color change to occur?

The timeframe varies, depending on individual digestion rates and the amount of food coloring consumed. It can range from a few hours to a couple of days.

Are there any other food colorings that might cause similar color changes?

Yes, other artificial food colorings can also influence stool color, often leading to unexpected hues. The interaction with gut bacteria and bile is unique to each dye.

Can I prevent this color change from happening?

Limiting consumption of artificial food colorings is the best way to minimize the chance of altered stool color. However, it’s not always possible to completely avoid this.